Update from South Africa

4 October 2023

Hello dear people,

We didn’t mean to let this much time go by without an update. But here we are. And here we are with notes from Hanna on her time in South Africa, with helpful footnotes by Marc. We close with a few points on the question, “How’s Hanna?”—highlights on her condition and experience.

Hanna writes…

I don’t know what to say about my time here in South africa. So I’ll start with the easy thing by giving you numbers. I spent 67 days here and slept in 14 different homes. I traveled far by car and plane, too many miles to count. And I visited with 80 people between the ages of 4 months and 97 years, sometimes one-on-one, sometimes in a small group. As I am writing this I feel tired and oh so-so-so-so enriched.

I was with my people and I love being with them. I had the joy of my family coming together, taking time off work, flying up, constructing temporary multi-generational homes, preparing feasts, playing games, exploring each other’s stories and life outside the playing games, exploring each other’s stories and life outside the stoep°. It soothed me in a deep way to see them step in as my ability to be a mom and companion recedes. We are cared for.

I was in my country, from visiting a township where people struggle to get by, to staying two nights in a fancy, fancy lodge. I got to be near, if not in, my medicine places—at the foot of a fynbos° mountain, at the edge of the sea with the salt spray in my face (and once falling into it by accident!), for a moment in tea-colored fynbos water, sitting at the ocean whale watching, noticing spring unfurl. The scent of dust and rain, the sight of the southern cross.

I got to have micro adventures, like my cousin borrowing a wheelchair from the hospice and pushing me on a thrilling ride on a red dirt down hill bike path°.

Marc's footnotes

Stoep

If you’re in the Western US, the porch. If you’re in the East, the stoop. Veranda, if you’re fancy.

Fynbos

An unbelievably diverse, dense, colorful, verdant mix of plants—bushes, grass, flowers—across the Western Cape of South Africa. When sage prairies of the Western US look at sexy magazines, they’re hoping for pictures of fynbos.

Thrilling ride

It is very fun to give Hanna a fast ride downhill in that sporty wheelchair. Imagine the thrill of wondering whether you can bring the whole package to a stop at the bottom of the slope. (Let’s not speak of the trip in the other direction, uphill through the fynbos.)

I got to celebrate two of my beloveds getting married and witness a community celebrating these two men’s love and union. And I got to dance with both grooms, our hearts and eyes flooding with love and laughter.

I loved being with your kids! Looking for chicken eggs in your garden. Drawing together. Holding the twin future Springboks.° Laughing together as the triplets danced. Listening to this person finding his or her way in the world. Seeing you in them and wondering who they will become, wishing I could stay to be here as they grow up.

I got to remember stories with my people. Jumping off cliffs at eighteen.° Burp-tennis championships°. The transition to post-apartheid. Our weddings and our college professors. I got to bear witness to my people’s lives: such joy and such difficulty.

I received the most tender care. My uncle making a fire° and filling a hot water bottle for my chilly feet.° My aunt sewing velcro on my pants so i no longer need a button. My cousin washing my back and my feet, holding my foot to her cheek while crying. My sister-in-law soaping up my body while making me laugh. My sister providing all the meds we need. and my mom, my always mother caring for me diligently and with such devotion, everyday she could.

Springboks

The South African National rugby team, of epic significance to the country. For one taste of the reasons why, see the movie Invictus. These twin babies were dressed in green Springbok onesies. One baby was smiling, one baby was crying, so no clear divination on the Bokke prospects this weekend against Ireland.

Cliff-jumping

I heard the story of this cliff-jumping from someone who was there, and who told the story at an amazing decibel level. He showed me a picture of the cliff. I think it was easily 100 feet high. “Every man who goes up there hesitates a long time before he jumps. Some of them decide they can’t do it. But not Hanna. She approached the edge and said, ‘Is this where people jump from?’ I said it was. Then she just took a step and jumped, without a thought about it.”

Burp tennis

I look you in the eye to make sure you’re ready. Then I swing my imaginary racket and give my best burp just when I contact the imaginary ball. Follow through is important. Now it’s coming to you. You burp-swing to return my serve. We keep going until one of us fails to burp. 15-Love.

Making a fire

With a propane blowtorch. Yes. I’m used to the idea that you try to start a fire with a single match—at least three sizes of wood between kindling and the big stuff, arranged in a careful lean-to. No stove or fireplace I saw in South Africa offered kindling. Just a stack of big logs and packs of kerosene-soaked biscuits called “fire starter.” And now here’s Hanna’s uncle, filling the stove with big chunks of wood, pushing a nozzle into their midst, and turning on the afterburner.

Hot water bottle

People kept offering me these! And I didn’t understand. We’d check into a guest house, and bottles would be waiting at the foot of the bed with little fuzzy coats on. Here’s the thing. It’s rare for a house in South Africa to have central heating. Winters aren’t cold-cold, but even so the sheets aren’t welcoming when it’s 6 Celsius / 43 Fahrenheit. So after a couple nights of Tundra-Boy prideful rejection, I tried going to bed with a hot fuzzy-coated rubber bottle at my feet. Pretty good, pretty good.

And we were the recipients of such generosity. Here, have my car. Here, stay in my home. Here, let me cook many meals for you. Here, let me spend a week with you, I’ll care for and drive you. Here, have my woolen shirt. Here, i’m going to fundraise so you don’t have to money-worry. Hey, I’ve shined your shoes. Not to mention the gifts you gave me that i will wrap and pack with care.°

I sought clarity on some past hurt, and sometimes received justification that confirmed the gap between us and other times truthful and healing words wove us closer together.

Some people could receive me in my grief and pain, walking me closer to embracing what is. Like my cousin talking me to a stream not too far from where her own baby died. He died in the same year as my miscarriage. And she held me as I deleted the pregnancy apps from my phone through my tears. Or you holding me as I wail and wail and wail for everything that I am losing. Or you staying present when I scream with frustration when i want you to hear but my mouth can no longer make words you can understand. Or when i choke and the smoothie burns like fire in my lungs and nose.

Many people, like my past self, have little practice in “grieving with the dying.” And it was difficult for me and for them too. I wrote a letter sharing my experience of feeling isolated in grief, and that led to healing conversations.

I walk away with a deep sense of connection to people and place. Having been nourished by you, I feel more ready to trust this withering away. My people in Pittsburgh have also been a stellar support system. i am returning to that home with a sense of their arms stretching across the ocean, like the light of the full moon on water, to welcome me

I also walk away with heartache. Many of the places we visited have since been scarred by floods, fires or massive waves. The camp we stayed at at Pilansberg, and hectares of veld around it, are now burnt to the ground. The Marina Beach cafe where you had your ice cream was smashed in by waves. The town of Stanford where we spent a night is under water—the worst floods in a hundred years.

Finally

The rest of this update takes a more serious tone, so I will stop these light-hearted footnotes. But before I go I want to tell you that there is one bird here that sounds just like those up-and-down slide whistles. “BEEEeeeooooo. booooEEEE?” And there’s another that yells like it’s afraid of heights.

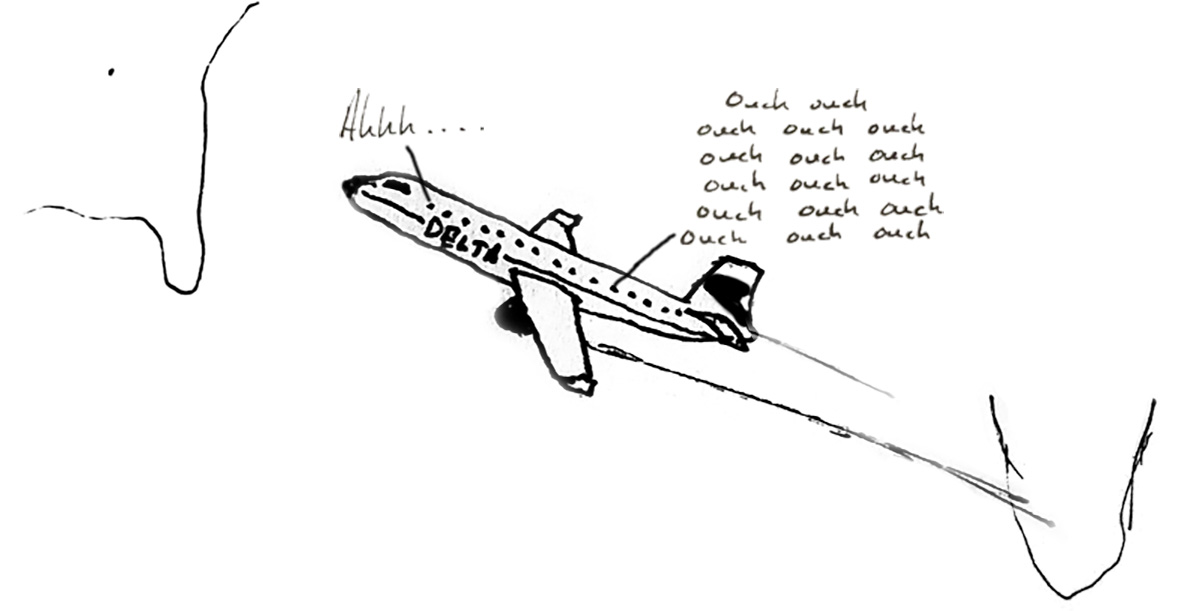

I feel the presence of climate catastrophe, a result of our modern life. And I know that I am contributing to it with all the miles I travel and my Western lifestyle. It is ironic for me, flying back to the US soon, that the airplanes and cars I rely on to bring me home are destroying the home of my body. (Here is an article linking environmental toxins to ALS).

Maybe that is the modern conundrum. I am not the only one in this sticky taffy. We all experience, to some degree, that what secures our comfort comes at the expense of something or someone else. The inequity in South Africa is a burning sore in my heart. I want for all people to feel safe enough and have their needs met, and we are so far from it. I acutely feel the urgency of working together over racial lines to heal and restore and rebuild.

But in my experience not many people share this urgency for action with me. Many people, like my past self, do not see a way to engage in shifting things. I’m not talking about being kind to black folks, or the fact that one has black friends or that one treats your domestic worker exceptionally well. I am talking about being engaged with others, across racial lines, in the work of facing the wounding of our past and the pain of the present and finding the healing and repairing action we need now. For while it is incredibly difficult, it is also sacred healing work that restores us to each other, that gives us back a sense of belonging and I hope, a chance for a thriving future.

It is my dying wish that everyone of us might find our role to play in healing and repairing past harms, and invest in the rainbow nation and beloved community. Smile. Yes, I am serious when I write this because I love you, your children and our country and I want y’all to thrive, together. I want everyone to feel at home, to be at home and not destroy the livelihood of others to do so.

I worry that I am sounding preachy. Please listen through my words to hear the deep ache for wholeness.

Addendum: How’s Hanna?

Some notes for those of you wondering about Hanna’s physical condition, her symptoms, how her ALS is progressing.

Hanna’s back is much better. So far as I know she has experienced only one spasm during the last three weeks.

But her core strength continues to weaken. She can’t really sit up in bed by herself any more. She needs the right support, and has to roll over and kneel on the floor to get up.

She can’t walk as far as she could when she came to Africa the end of July. Maybe half as far, and then she needs support.

Hanna can no longer wash her own hair or under her arms. She feels her arms are weakening significantly. Her left hand is much weaker than her right.

Because of all this, she needs someone to dry her after a shower, and help her get dressed. Eating is becoming increasingly difficult and messy. She needs help cutting food.

This will eventually affect her use of technology for creating and communicating. She continues to write almost daily on her laptop. We have begun the process of identifying and acquiring eye-tracking tech (“I can type with my eyes!”) so she can begin practicing its use for communication, writing, web surfing, entertainment, etc.

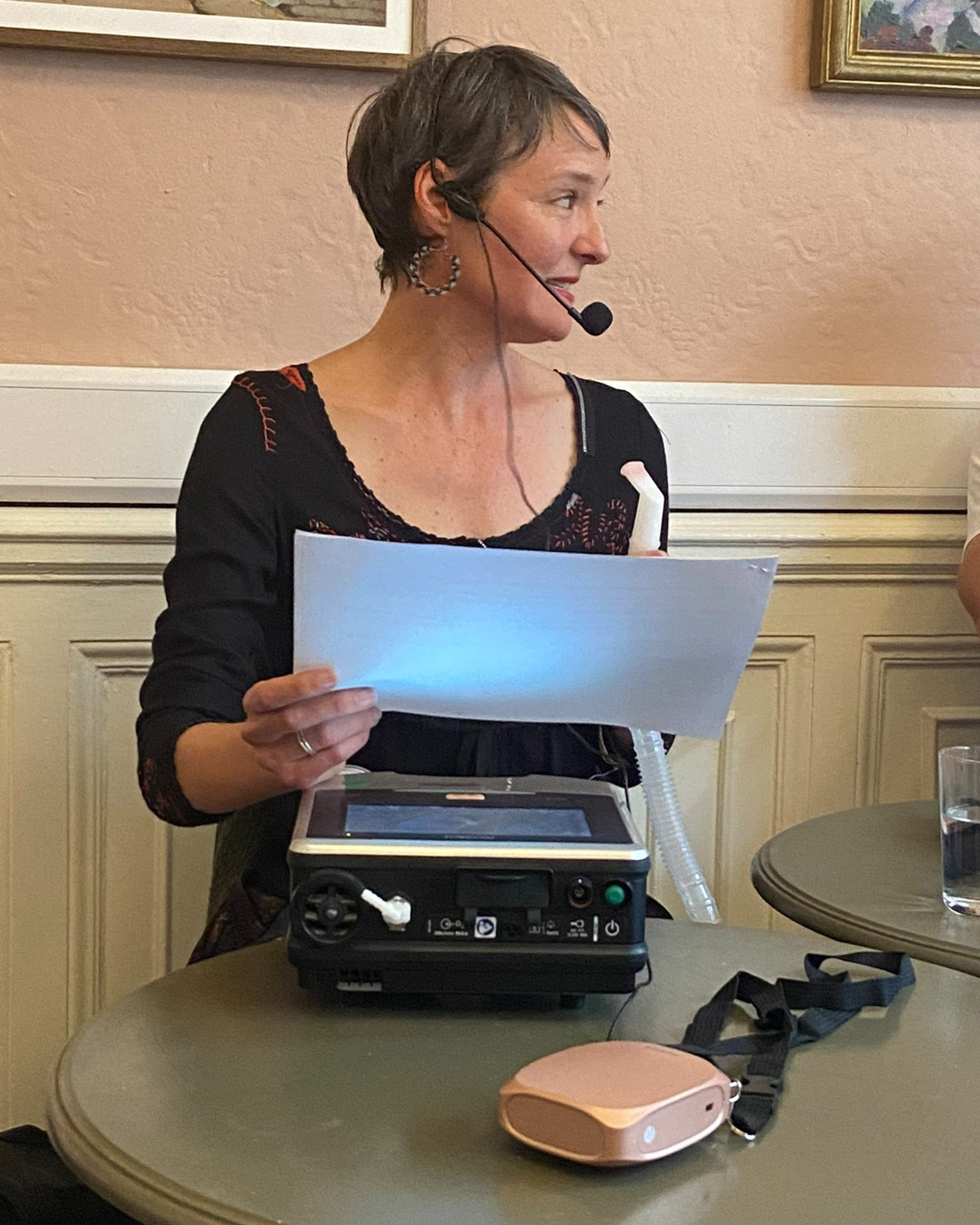

And it continues to become more difficult for Hanna’s to communicate with speech. It takes effort for her to be clear, sometimes even with people who talk with her every day. Tools like the speech tablet and “Boogie board” erasable writing tablet are hugely useful.

Update: Back pain, South Africa, and tadpoles

24 August 2023

Hello dear friends,

Here is an update that mixes words from me and Hanna. The biggest topics this month have been her back pains and her time in South Africa. To avoid confusion, I’ll put my own words in italics, and Hanna’s in regular type.

Oh, and this—people have commented on past updates saying they want pictures of the pet tadpoles and preying mantis. I aim to please. See the gallery at the end of this update.

Hanna hurt her back

In early July, Hanna had her first ambulance ride of her life. Earlier that day she and Seth went canoeing. There was a moment when she leaned back, expecting support, and there was none. Pow. Hours later the pain was still great, and it was ambulance time.

Hanna’s back problems started two decades ago. She says,

I would have occasional episodes of pain that would a couple of days. They were bad enough to land me in bed—it was too painful to move. But they would eventually wash over and away, and I would be back to an active life.

The condition worsened during the pandemic, leading me to specialists and x-rays. I was diagnosed with degenerative disk disease, and the only way to combat this condition is to strengthen my core. So I began to swim again, and do daily exercises. But ALS weakens your muscles, and Bulbar-onset ALS starts that weakening in your core.

After the canoe trip, her back would go into a spasm when she moved. Here’s how Hanna describes those hours after the canoe incident.

My spasms changed from occasional short episodes to endurance contests lasting… god knows how long. Seth says an hour. I was gripped in pain, howling, panting, shaking uncontrollably in my whole body. Snot and tears everywhere. Like a scared animal, Seth says. They finally started to settle when Seth brought my breathing machine. The shaking lasted all the way to the emergency room, where the wonderful staff provided care and a shot of valium.

The cosmic wires got crossed! I was asking for a whole-body orgasm, but with my poor speech they heard “whole-body spasm.” Thanks ALS 🙂

She jokes, but the weeks after were difficult. Try to sit up: back spasm. Someone tells a funny joke: back spasm. Sneeze: back spasm. And so on. This led to the core group of folks around Hanna to organize full-time care. We set up a schedule, and made sure that someone was there all the time.

Two falls

Every time I visit the ALS clinic, they ask this question: “Have you fallen yet?” They ask because your first real fall signifies the beginning of a different chapter. The end of mobile freedom. Your future is now splattered with grab bars, handrails, sharp furniture edges wrapped in foam, walkers, wheelchairs.

Less than a week after the trip to the ER, Hanna had her first fall. She fell in her bedroom, and landed on her back. Mercifully nothing broke. But it did re-injure her back, making it impossible to sit up and finish a meal without a spasm yanking her off the chair.

The back pain continued and sometimes spiked. Over time the episodes became less frequent and less severe. And now she is feeling better.

The second fall was in South Africa, where she has been with family since the last days of July. She fell down some stairs, arrived at the landing at the bottom of those stairs, then continued down the next flight. !! Again, we feel so grateful that the damage was marginal: a sore and swollen ankle, some scratches and bruises. Lizzie lent her a cane that she uses on and off and Elsa borrowed a walker for her to use.

Eish! (as they say in South Africa)

Hanna in South Africa

I haven’t said a peep lately. In part because I was knackered. In part because I am having a hard time typing. My left hand is becoming a rake. And in part because I am able to do less and less with the time I have. Seth is helping me dress and perform tasks like opening a tube of toothpaste.

I want to say a few things.

IT IS WONDERFUL TO BE HOME

The familiarity of the things I grew up with meets me like a receiver meets a telephone (That’s a line from Seth’s daughter Early.) The familiar brands I see in the pantry, like Black Cat peanut butter. The taste of Boerekos (“farmer’s food”)—pannekoek, sosaties en pap. The scent of spring in a jasmine flower or a braai at the boeremark (In South Africa they don’t barbecue, they braai). The shape of familiar trees like a kapok boom. The sound of my family laughing around the dark wooden dinner table.

IT IS A JOY TO BRIDGE MY WORLDS

It has been such a delight to have my worlds meet and enjoy each other. Rachel (my niece) is 11—a year older than Early and a year younger than Otto. Together they are a wild fire and a whirlwind of excitement and laughter. My SA family have been exceedingly wonderful hosts. My mom brought us breakfast in bed, my dad braaied a beautiful Sunday lunch and now we’re at my sister’s. She ordered pizza and made one of my favorite desserts—a peppermint crisp tart.

IT REMAINS A CHALLENGE TO BE ILL

This afternoon I sat in a block of sun light. I couldn’t see the shadow move, but twenty minutes later the patch of light had crept over my legs and fallen onto the floor beside the bed. ALS is like that. My body has changed so much in the last seven months. Being back home but not being as able as I was before illuminates the change. The most difficult thing is to speak and not be understood. The second is the diminishing capacity to walk, run or climb with confidence. And tied to that, the use my hands.

The saddest moment of our trip was being at the sea. The water was rough, the waves were high. In my usual form I would run into the wildness and play in the waves like a seal. But i couldn’t. The best I could do was stand in the water, holding onto Seth so I didn’t lose my balance and fall in.

I am reminded everyday of good principles to live by, like “one day and one symptom at a time,” and “grieve what is lost and then focus on what is possible.” I remind myself that I even though I have a sense of this illness’ progression, I have no idea what awaits, including wonderful things.

CONTINUED GRATITUDE!

In the moments after I tumbled down the stairs, I felt so much support and care. I remembered Mr. Rogers’ saying, “Look for the helpers.” But my cynicism slid in said, “Ja, they are here now. But they’ll be off playing mini-golf tomorrow and you’ll be all alone.” Not long after I opened my email and saw your air miles rolling in. And I thought, “You are wrong, cynicism.”

Ya’ll’s love and support is life-giving. Thank you to everyone who helps logistically, who makes me food, who offered me their Delta miles! Thank you for financial support (my ventilator’s humidifier broke, I need adaptive undies, my home needs equipment, I need a hand brace and a retainer to help with swallowing, etc. etc. And thanks to you I am able to meet my needs.

I want to write you all love notes, but my energy doesn’t match my intention. Please take this as a personal note of thanks!

I promised you tadpoles and mantises…

Delta air miles to help Hanna?

UPDATE: Tickets secured!

After a looooong struggle and dance with Delta’s systems, which included having Hanna’s account flagged for possible fraud because of all the miles gifts that were coming in, we’ve had a breakthrough. A member of this community reached out to someone Most Senior in Delta, and within a few minutes all the needed flights were secured.

What a gift. Sheesh.

Systems can’t care. People can. I spent uncounted hours at my desk and nearly four hours on the phone with people whose ability to care is limited by policies and processes. The architects of those policies and processes necessarily work in broad strokes that cover most typical cases. The need to defend against fraud is understandable, but those defenses prevented the people I spoke with from acting on their desire to care.

Things didn’t loosen up until we spoke with someone who had the power to act outside the system, outside the broad-stroke processes. Once we found that someone, she waved a wand and Poof! Confirmed flights.

(Huge thanks to Amanda, who had the idea and follow-through to make this happen. Huge thanks to Susanna at Delta, who has a magic wand and who wields it with love.)

Original post follows below.

14 August 2023

Hello,

This is a short-term request for a very specific kind of support. Here’s the situation in nice businesslike bullet points, just like the ones they use in presidential briefings….

• Hanna is in South Africa with family, friends, and all the creatures and memories of her home.

• She is experiencing sporadic and quite difficult back pains. These started two decades ago, continued off and on, worsened during the pandemic. As ALS weakens her core, the back issues are becoming more persistent.

• A dear friend worked conversational magic to score Hanna a lie-flat bed in the first-class cabin to South Africa. That’s the ONLY way to make a seventeen-hour flight possible for her.

• Now we are working on making the same arrangement for Hanna’s return flight, without spending the $8,000+ required for a first-class seat. We’ve had the brainstorm of using air miles. The price in miles? 495,000.

Well, we thought we’d try.

If you have accumulated air miles on Delta or one of its partner airlines, and would be willing to donate some of them toward this possibility for Hanna, please contact Marc Rettig before the morning of Thursday, August 17.

Thank you, fellow sailors on these seas.

Marc

Short update: Hanna in SA + event summary

31 July 2023

Hello all,

This is Marc, with a short update. Some are wanting to know how things went with Hanna’s trip to South Africa, and some have asked about the event we announced in the previous update. Here’s a wee bit about those two things.

Successful landing in South Africa

Hanna, Seth and the kids have safely arrived in South Africa, They are now in the wide strong arms of family and friends there.

Thanks to the efforts of the “TLC team,” especially Erika aka “Goldie,” Hanna had a first class seat for the 17-hour flight from Atlanta to Johannesburg. Given the way her back troubles have been flaming up, this was really the gift that made the whole trip possible.

Report on “Design for the Inevitable” workshop

As we mentioned last time, Hanna and I held a conversation hosted by the Pittsburgh chapter of the Interaction Design Association. Our friends Raelynn and Ashley, partners in the design firm Dezudio, wrote a really great summary of the event.

Read Raelynn and Ashley’s report here.

Debriefing after the event, Hanna and I shared a few ways this evening felt important.

– It felt sooo good to be hosting these profound conversations together. This has been our work for more than a decade, and it still feels right.

– This exploration of how our collective creative work might embrace the “shadow” aspects of human experience is hugely important for our times. We’d like to engage more with these questions. And we will.

Thanks to Jack Moffett and the rest of IxDA Pittsburgh, and warm gratitude to Ashley and Raelynn for writing such a great summary.

More soon; ways to help

We’ll send a more detailed update soon. I know I’ve not said anything this time about symptoms (some progression), morale (usually high), or needs (thanks to soooo many). And there are announcements coming about publication of Hanna’s writing and work. (Preview: see the new main page of okaythen.net.)

Since Hanna is in South Africa, the Pittsburgh food train is turned off until her return. Meanwhile we continue to collect and save against future expenses. You can find links for that here: okaythen.net/hanna/hanna-help.

Thank you all. Here’s wishing you good flow and an open heart in your dance with what life is bringing you.

Marc

“Establishing a relationship with grief, developing practices that keep us steady in times of distress, and staying present in our adult selves are among the central tasks in our apprenticeship with sorrow. This is the hard work of maturation. In the traditional language of apprenticeship, this would be called achieving mastery. In the language of soul, this is the work of becoming an elder. An elder is able to touch grief deftly and is able to craft sorrow into something nourishing for the community. Teacher and grief specialist Stephen Jenkinson says, ‘Hold your sorrow to a degree of eloquence, whereby everyone around you will be fed by your efforts to do so.’ Becoming skillful at digesting our grief makes us a source of reassurance and stability for the wider community.”

Francis Weller, Wild Edge of Sorrow

Update: back from Ireland, ALS is always moving

Pittsburgh people: Hanna and Marc are hosting a conversation the evening of Monday, July 17. Come join us!

12 July 2023

Hello sweet people,

This is Marc, with an update on many aspects of Hanna’s life, progress, and needs. I’m working from an outline that Hanna provided—these are my words but it’s her story. The headlines:

– Ireland was great! There is so much to be grateful for.

– ALS is always moving

– July: lots of doctor visits, and some needs

– What’s next: South Africa!

Ireland was the best thing ever!

If you’ve followed the updates you know that Hanna was in Ireland on scholarship from Carlow University. She had two great weeks of writing instruction, coaching, and community. Each morning she had a session with a mentor. Then most days lunch, naps, writing and energy maintenance filled the rest of the time. There were a few adventures and explorations in Dublin, and a few days after the workshops to travel to Sligo. What was there? Roads and fields lined with stone, goats, horse carts, green landscape, and the sea.

Hanna says it felt like a vacation from ALS. She’s home now, reconnected with the logistics of living with a healthcare system that requires hours of labor and attention in order to receive its benefits. Also she’s reconnected with the wide strong arms of caring friends and loved ones.

Hanna’s lists…

Feeling such gratitude for everything that did not happen in Ireland

– No COVID: Coming home and putting the unneeded COVID meds back in the medicine cabinet. The exposure of long flights feels risky, and COVID would be a huge setback. All good!

– No falls: There was no need to use gauze and tape as she didn’t fall! (She had a few near misses, but the bruises on her right arm tell the story of a good catch.)

– No pain: Her back didn’t hurt until she came back, so put those pain meds away.

– No diarrhea, no loss of appetite or weight

Feeling so incredibly grateful for all your contributions!

– Everyone who helped getting ready for the trip.

– Everyone who contributed financially.

– People who took care of SO many details (power converter, smoothie maker, sufficient supply of medicine, communicating needs to airlines, researching and acquiring communication aids, getting pants that fit! To name only a few)

– Help with so many expenses (international phone plan, medical travel insurance, cost of being there…)

ALS is always moving: this is a time of transition

Hanna’s mom was here with her for a month, and soon after came the trip to Ireland. Now that season has ended, and as she cares for herself Hanna is finding that her body’s regression is more clear.

– Her hands are getting more clumsy. She dropped her glasses, broke a very special bowl, burned herself.

– Her core is weakening. Standing is becoming more difficult, which makes cooking and cleaning more difficult.

– Standing up from a seated position is becoming more challenging. Getting down on the floor and getting back up from the floor is becoming really difficult.

– Weight: Hanna gained weight in Ireland . Was it the baked beans and eggs at “The Buttery” or the fish and chips or the half-pints of Guinness? When she returned home, Hanna started losing weight. One response: we are adding more “Give in Kind” slots for food delivery in the rest of July.

Looking forward into the Autumn, Hanna might need to transition to more full-time care, as dressing and basic hygiene are also becoming difficult. Her space also needs adjustments to be more disabled-friendly. There are services out there for this kind of help. We are learning how to tap them and making our way through the process of qualifying and registering. And we are scoping out possibilities for a more accessible place for Hanna to live.

July holds many doctor’s appointments

– Pulmanologist to check in on how she and her lungs are doing

– The ALS clinic for a meeting with the whole team there

– A preliminary visit with a surgeon to discuss the feeding tube operation

– A check up with her primary care physician

– Another swallow study as her choking is increasing quite a bit

– Hopefully a consultation with a doctor about her back pain

Help in July–open slots for meals

Might you sign up for food delivery?

We’ve added more slots, which you can see if you scroll down on the Give In Kind page. It’s easy to sign up, and you can either bring food to Hanna’s house, arrange for a delivery, or send a gift card. (Do read the “Special Notes” above the calendar before you decide on the food.)

What’s next?

Hanna will be in South Africa through August and September. Seth and the kids will join her for a few weeks in the beginning, and Marc will join her in September.

In preparation, we’re working to get the right insurance in place, acquire and configure a tablet that can help her communicate in both English and Afrikaans, and generally do all we can to smooth her travel and support a joyful experience.

“How are YOU?”

A friend sent me a note last week that simply read, “How are you?” That was the whole note. I get that question pretty often. A concerned tone: “How are YOU?”

One

I walked to Hanna’s place to pick up some papers. When I arrived I found another dear friend getting out of her car to visit. As we were about to go into Hanna’s house, another car pulled up. A third friend! We went up the stairs together, and so started a kind of party. Catching up on news, eating snacks from five different countries. The door opened—it’s a fourth friend! Mixing gin and tonics. Hanna’s boyfriend Seth arrived. Conversation swirls, people clearly love each other. We discuss what games might create a level playing field for everyone, regardless of speech ability and hand strength. What if everyone has to use a speech app? A load of laundry gets done, the kitchen is swept, the tadpoles and pet mantis are fed.

We are woven into a fabric, able to hold grief and joy at the same time.

Two

I have email from a relative. We enjoy and love one another, but don’t communicate very often. She says, “I understand that life is not happy for you with the worry of Hanna and I dread to think how she feels.” In composing a response, it’s not only that I want to assure her that “life is not happy” is the wrong picture. It’s that I would like to offer her the possibility of a relationship with loss and death other than worry, unhappiness, and dread.

It is possible to accept that there are torpedoes, but refuse to sink.

I wish that woven fabric and sturdy buoyancy for her. And for you. Tight fabric, few torpedoes, and buoyant life to you.

Marc

Now: A Season of Grief and Gratitude

Featured season

Season of grief and gratitude

[this is a post stub]

Update: new gear, travels, and bountiful support

14 June 2023

Hello dear people.

This is Marc writing. It has been about a month since the last “How’s Hanna?” update. SO much has happened. Hanna’s mom was here much of that time, and other family has visited. There were outings—to a cabin in the woods, to “The Ruins,” to tables and porches and gardens and ponds all around. And seemingly bottomless engagement with systems and infrastructures of care.

I’ve talked with a few of you recently, and heard some common questions. Maybe those questions are a good guide for this update.

How is Hanna?

The surface, physical answer is “pretty great for someone with a terminal diagnosis.” She notices some progression of her symptoms—speech difficulty, strength, breath, energy. At the same time the routines of sleep and energy, diet and weight are paying off. She has gained ten pounds since her low point in March. Her days have many moments of joy, she’s getting things done. I imagine she would say she can’t do everything she wants or thinks she should do. But if you’re distant from Hanna you should think of her as someone still very much engaged in life.

New gear aplenty

Over the past month, a lot of helpful gear has arrived at Chez du Plessis. A few are helpful on the voice and communication front. This includes a “boogie board”—a thin, butt-simple tablet for quick messages like, “A small oat milk latte please” or, “Baie dankie, my skattebol.”

There’s an iPhone app called Speech Assistant that makes it quick for Hanna to type things which the app then speaks out loud. It uses a proper-sounding English-accented lady voice that I find pretty amusing.

And thirdly, Hanna has a voice amplifier like you might see someone using who’s leading an exercise class. It has a thin headset microphone and a not-too-big amplifier and speaker on a strap. She can wear it around her neck and be heard in a large room or at a noisy dinner without working hard to raise her voice. We learned from a speech pathologist that the effort to be heard contributes to Hanna’s depleted energy at the end of the day. This voice amplifier helps.

And there’s more! The arrival of the ventilator and cough-assist device was a big day. When you hear “ventilator” you might picture someone at a hospital hooked up to a machine that breathes for them. This is not that. This is portable, much like a CPAP device for people with sleep apnea. Hanna can use it at night with a mask to help her breathe well while sleeping, or she can use it during the day with an attachment that looks like the stem of an oversized smoking pipe. If she’s talking a lot or otherwise feels short of breath, she can put that in her mouth, inhale, and the ventilator helps by providing pressure. She gets deeper breaths with less effort. More blood oxygen, more energy, better days.

Which is all great. At the same time, all these devices are reminders that Hanna is someone who needs them. The day of the ventilator’s arrival was emotional. Difficult. It’s wonderful to have good deep breaths, it’s wonderful to be understood and participate in conversations. And it’s difficult to realize you need help with these basic aspects of life.

How is Hanna? Stubbornly joyful.

How did Creative Mornings go?

It was really great. It was moving, profound, and very huggy. They are working to edit a video of the session. We’ll post it here as soon as it’s available. Meanwhile here’s a photo gallery.

How is Hanna doing in Ireland?

Things definitely got better after the trial of getting there (here’s her story about that, in case you haven’t seen). I’m sure she’ll tell us in her own words before long. I’ll briefly report that she’s in writing workshop every morning, taking time to write outside of that, and when her energy budget allows she’s getting a taste of campus and country. I know this isn’t telling you much. Just wanted you to know that so far the trip there was the hardest part, and it sounds like the time there has been rich and rewarding.

So is the diagnosis final then? Still having tests?

Yes, the diagnosis is final. There’s a rhythm of visiting the ALS Clinic every three months, engaging the clinic’s various specialists as needed in between. Clinic visits include a breathing test and strength tests as well as a standard protocol that’s repeated each visit to monitor progress of symptoms. When Hanna returns from Ireland she will begin a new medication (“tastes like bunny dook!”) which for many people slows progression and extends life.

I hope it’s okay to ask, but how’s the money situation?

The short answer: this is currently not a source of stress, and there has been incredible progress.

The longer answer: we’ve made great progress in enrolling Hanna in programs that qualify her for different kinds of insurance (hello, Medicaid), which will greatly reduce or eliminate some of the most expensive co-pays. There’s still work to do on this front, but things are falling into place.

Then there are expenses we can only anticipate without knowing when they will arise. That’s why we started the donation fund last month, and…

Holy smokes, you all. The generosity. The fund is now just short of $18,000. More than half of that came from two donors. The care, connection, and generosity has left me speechless and has touched Hanna so deeply.

I can feel embarrassed by this bounty. I talked with my neighbor about this. She is a cancer survivor, well familiar with what it’s like to navigate the finances of a serious illness. Her advice to me: “It’s too early to relax. Don’t say no to offers of help, thinking you’ve got it covered. There will come a time when the costs go up and the story is no longer a fresh concern for people. You’ll need everything you can gather.”

As a bright-side-looker, I feel it’s important to hear balancing lessons like this. So we’re going to leave the donation link up. A thorough and humble thank you to all who’ve given in this way. (And others in so many other ways!)

Thank you. Thank you.

Marc

There is a brokenness

out of which comes the unbroken

A shatteredness

out of which blooms the unshatterable

There is a sorrow

beyond all grief which leads to joy

And a fragility

out of whose depths emerges strength

There is a hollow space

too vast for words

Through which we pass with each loss

out of whose darkness

we are sanctioned into being

There is a cry deeper than all sound

whose serrated edges cut the heart

as we break open

to the place inside us

which is unbreakable and whole.

All the while learning to sing.

Rashani

Traveling to Ireland

Where is Hanna now? Trinity College Dublin.

Traveling to Ireland

This past Saturday, Hanna set out for two weeks of writer’s residency at Trinity College Dublin, sponsored by the writing program at Carlow University. That day also marked the end of long lovely days with her Mom, Elsa, who had been in Pittsburgh for almost a month. Here is Hanna’s travel report.

I like leaving for a trip, but this time I like it even more because I am leaving behind the many reminders of my illness and of a future I still grapple to embrace—the five boxes of medication I start when I return from my trip. The outside walker. The slanted stacks of papers from the medical maze. The unopened and unassembled shower chair for when standing showers becomes too difficult. The plastic arm to help the ventilator pipe fit onto a wheelchair.

But I’ve never before attempted international travel while terminally ill. After check-in and a last long lean into my mother’s arms, my body buckles into a wheelchair. Surely this is not my first time being wheeled around. I’ve been in strollers, on bike handlebars, in wheelbarrows. But today it is my adult independent self that is asked to sit and be moved by someone else. For a moment I want to brace—fasten a seatbelt or hold the handlebars. But Kim, the person at my back, pushes just slowly enough for me to trust the ride.

My beautiful body reads the different floor textures like braille. The coaster-sized porcelain tiles with their wide lines of grout reverberate like cobblestones. The expansion joints in the terrazzo floor are so delicate, I need to listen with my entirety to feel them. The aluminum plates that hide underfloor cables make for hiccups in the ride. And the rug feels soft, almost like sand slowing us down.

At the gate they need me to check my carry-on, but my ventilator is in it. “Take the ventilator out,” they say, “and then check the bag.”

“No,” I say, “the ventilator pipes are too fragile and will get damaged in my soft-shell bag.”

“Okay, okay. You can have it on the plane.”

Thank goodness I can still speak.

I didn’t book my tickets for this trip, the school booked them for me. They put me on the same flight as Donna, another Carlow student. We have a six-hour layover, and Donna had booked a lounge suite where we could pass the time. After we disembark in Philly, I see Donna only briefly. The airline had checked her bag through from Pittsburgh to Dublin. But they told me that they couldn’t book mine through in the same way. I would need to pick it up in Philly baggage claim during the layover, then recheck it to Dublin. With a wheelchair.

I tell Donna that I must get my bag before meeting her at the lounge. Then Breeze the airline assistant wheels me away.

We get my bag at the luggage claim and take it to the airline that brought me to Philly. “Oh no, sorry,” they say. “This ticket is two separate bookings. We can’t check your bag, you must go to Terminal A.”

Breeze whisks me away and suddenly we are at security. “Shouldn’t we go to Terminal A first?” I ask.

“We’re going there,” she replies. I’m confused. In my mind you check your bag before you go through security.

TSA screens my large bag, the one I’m planning to check. A blonde guy with blue gloves works his way through my belongings, and I feel angry as he unwraps my stuff, opens my candle and smells it. He takes out the protein powders to screen them. Sets aside my protein shakes and takes apart my blender.

“But I want to check the bag, not take it on the plane,” I say, confused.

“But you can’t take these through this security point.”

But I don’t want to go through security. I just want to check my darn bag and then go through security without it. Another lady jumps into our confusion and amplifies it with unsolicited advice. My eyes burn with frustration and simultaneously I feel ashamed that something so small can make this white lady cry.

“Are you okay?” asks Breeze.

“Yes, yes,” I say.

TSA man restates the facts. “Either you leave the shakes and blender here, or go back and check your bag.”

We turn around to go to Terminal A without going through security. “How do we get there?” I ask.

“We walk,” Breeze replies. Walking turns out to be a rotten task with me, two bags on my lap and Breeze—weighing no more than a suitcase herself—tries to push me in an old wheelchair while also dragging my 46-pound bag behind her.

“Wait Breeze,” I say. “I can walk. Let’s work this out.” I get up and push my carry-on bags perched on the wheelchair. Breeze brings the large bag. If I had studied Philly’s airport, I would have known that Terminal A is quite far from Terminal F and that a shuttle would have been a smarter plan. Maybe not for a fit self, but definitely for this self! I stop a couple of times to catch my breath.

When we arrive at Terminal A, hot and sweaty, I am well positioned for a temper tantrum. It’s nap time, I’ve not had lunch, I am thirsty and tired. If you have ALS, it is important that you rest, hydrate and eat regularly. I can’t wait to check this bag, slip through security to food, naps and water.

But bad news awaits. The airline that must check my bag to Dublin won’t open for two-and-a-half hours. The terminal is a single room, with no bathroom and nowhere to buy food. Since Breeze and I can think of no other practical option, she leaves the wheelchair with me and goes on with her day.

The first airline’s job to hand me over to the next airline is done. I take my place on the fake leather seat and watch my mind throw a temper tantrum.

If I was able-bodied I would have found a way out of there to food and water, at least. But I am not. Our world is not set up to take genuine care. The first airline, knowing of my condition, hearing my request to book my bag through to Dublin and my need for a wheelchair, did not think in terms of care. Even though checking a bag all the way through was possible—my travel companion with the exact same travel plan had done just that—Breeze (an employee of that airline) was not empowered to think strategically with me.

And so I landed in the seam, in the crack between two airlines who had done their duty, and who had no further responsibility toward me.

What is the impact of landing in this unsupported and unseen no-mans-land? The lack of water makes my mucus thick so I can gag on it. It worsens the fasciculations in my body, making it harder to sleep. And contributes to constipation and ass-figs (also known as hemorrhoids). My body hopefully meets its need for protein and calories by taking from my belly fat rather than muscles or organs. My tiredness will be passed onto my future self. (And it was. I was so exhausted upon arrival that I could hardly muster the energy to chew my sandwich.)

All of this is manageable. At least this time and for this person. But what about all the others who have slipped through the cracks?

Once I stood in front of a glass case in the national history museum of Mexico, looking at a figure carved out of rock. The description said that once very, very, very long ago, people who were born with Down’s Syndrome were considered gods. Imagine that! Imagine if tomorrow everyone on the margins woke with garland of flowers and prayers and incense around them. Imagine their joy as they stepped or rolled or stumbled into a world so tightly woven together in reverence for life that they never feared slipping through the cracks ever again?

Event: Hanna at Creative Mornings Pittsburgh, 26 May

Hanna will be speaking at Creative Mornings this Friday.

Hello,

This one goes out to those in the Pittsburgh area. Hanna will be the featured speaker this Friday for the Creative Mornings event. It’s, you know, Creative Mornings, so if you want to start your day with coffee, interesting folks, and Hanna, it all starts at 8:30am.

Here’s the place for to see the details and sign up for a free ticket.

See summa yinz there!

Marc

How to get through the first 17 hours after learning you have ALS

Getting through the first seventeen hours

after learning you might have ALS:

a how-to guide

1. Take a notebook and pen—one that works—to the doctor’s appointment. When the doctor looks down and sighs as if she’s trying to shed the heaviness you both feel, be sure to have both pen and paper ready. Listen carefully as she says, “I suspect you have ALS.” In that moment your brain might not be working right. That is okay. Try to focus on her words and make the symbols for ALS as many times as needed. She will nod in agreement when her sounds and your scribbles align.

2. Walk out of the appointment and search for your phone. Text the friends who marked their calendars with “After doctor support.” Tell them to meet you at the bar.

3. Arrive. It’s okay to feel out of sync with all the people giggling around you. Let your friend choose a table. Excuse yourself and visit the restroom. Be mindful, if the bathrooms are gendered, to choose the one that matches yours. Sit down on the toilet seat and cry. If there is no one else or if you feel okay with someone hearing, cry loudly. Then pee. Wash your hands, wipe your face. Wink at yourself. Apply lipstick if that’ll make you feel stronger. Take a tissue to the table.

4. Join your friends at the table. Be sure to sit where you feel most held. A corner seat is good for that. Allow your friends to order you a drink and choose the appetizers. It’s okay if you forget to consider the happy hour menu.

5. Ask the questions. This is a good place to ask things. You are not alone now and your friend who holds the world of Google can be trusted to translate. Ask anything. “How long is the average time to live?” “Will I die of suffocation?”

6. Cry. It’s likely that you don’t often cry in public, but this is the time to break that taboo. Lower your face into the brown paper napkin. Let sorrow rise from inside you. Let it shake your shoulders and escape the narrow passage of your throat.

7. Ask for jokes. When you start to feel like you are sinking below the surface, ask your friends to tell you jokes. Laugh at all of them, even the dick joke. Search for a joke inside your own mind. It must be there. Allow your laughter to swing into crying and then back into laughter again. If you have never faced death like today, your emotions need a lot of space to roam.

8. Eat at least ten bites. Your belly will constrict with fear. But all these weeks of tests and waiting have already worn you thin. You need sustenance. Take two french fries between your fingers and dip one in the mayo, one in the ketchup as if they are legs with different colored socks. Chew. Taste the tang. If necessary, use water to help you swallow.

9. Hug your friends goodbye. Notice their bodies close to yours. Let your nose rest on her buzz cut and breathe in that comforting scent. Feel how thin he feels after his open-heart surgery. Cusp your hand over his soft, warm cheek. Don’t let go of his hand until you split off into your own apartment.

10. Sit down. It’s okay if you forget to take off your coat and hat, but do remove your gloves. While I want to advise you not to google ALS in this moment, it might be very difficult to refrain from doing so. Set your timer for fifteen minutes.

11. Answer the phone. When your partner calls, answer. Be honest when he asks you how you are. This is not the time to “be strong.” Allow him to come over, you may really need the company. And he might too.

12. Bathe. Do the thing that will bring you most comfort. If you’re able, I suggest taking a fragrant bath in candlelight. Lift his shirt from his body with your able hands. Untie his belt. Stay close to him as you both step into the water together and lower your bodies down. Roll the soap between your hands and watch it froth. Transfer the soapy foam onto a washrag and place it in the nape of his neck. Draw it down as you trace the shape and strength of body under your hands. Wash his whole body with this careful attention and let him reciprocate. Let him wash down the tears brought on by the thought of no longer being here to hold or be held by him.

13a. Try to sleep. Take some of the sleeping drops your friend who is going through chemo gave you. Lie awake. Reach for and turn to each other. Make love. Watch as your mind leaves this moment and goes to your death. The dying moments where you lie, alone and plumbed through with pipes on creaky white sheets, holding onto this moment. Don’t stay there. Turn around and swim through the viscous night. Swim right back into this moment, this moment where your lips are still working, where you can kiss him still.

13b Try to sleep. When you can’t, sit up and look at the cascading handrail of the city steps and the long power lines glistening in the tungsten street light. So thin, like spider webs.

13c. Try to sleep. Walk down to the kitchen and ask the stove to tell you the time. When you learn it’s 2 am, hunch down and look at the dying embers in the fireplace.

13d. Try to go to sleep again. This time visit the bathroom. Don’t be surprised if your period has started weeks too early. Bodies do this when they feel panicked.

13e. Try to sleep. And when you can’t, get up and make yourself a cup of hot water. If your belly aches, eat half a banana while you watch the cat curled up, now a contoured button on the corner of the rug.

13f. Try to sleep again. Feel the relief wash over you when the sky begins to shed its darkness, when you can tell you made it to the morning.

14. Turn to each other. Hold each other tightly as both of your bodies shake in sadness, as you wake into the day neither of you ever wanted.

15. Then roll out of that warmth towards the edge of the bed. Lift the covers. As you come to a seated position, swing your legs out of the bed. Feel your feet on the wooden floor. Lift your weight up onto your feet.

Congratulations. Not only have you survived these hours, you are also practicing the thing that will keep you going in the coming passage: standing up, physically or not, and beginning again.